“Poetically Man Dwells.” – Martin Heidegger

Temporary and lasting

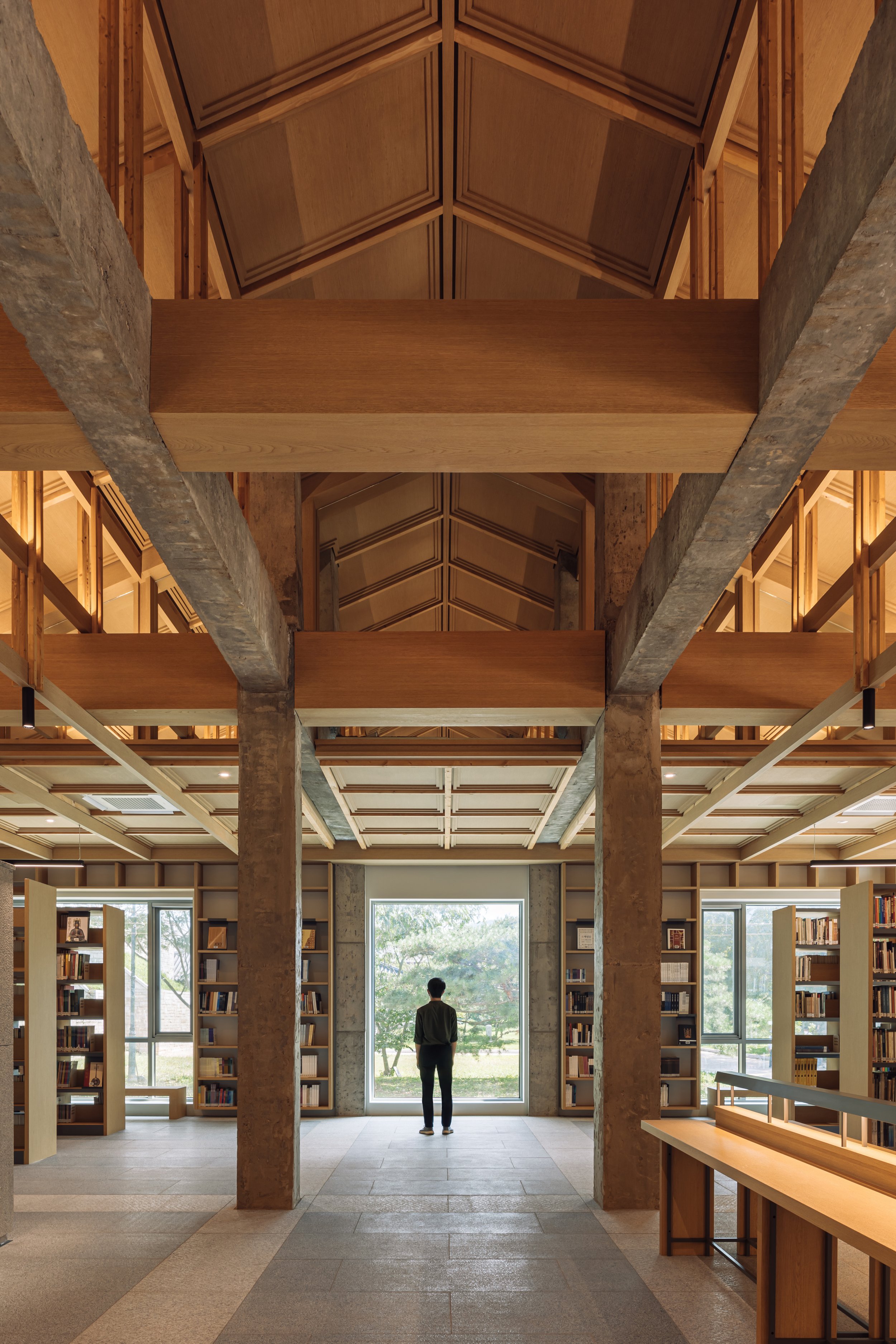

The land lies at the foot of the western part of the river where the North and South Han Rivers converge. Forty years ago, the land owner had sought to build a house on this land, which had been long untouched by humans and had formed a lush forest of old trees and growing shrubs. One can reach the riverside after taking a long narrow path through the bushes, seeing the river flow silently over the wind-stirred reeds and the hem of Jungam Mountain laying upon it, just like an old Korean painting. The early morning mist of the water is scattered in the sun, and groups of birds fly overhead, the flapping of their wings being the only sound in the otherwise calm silence. On the edge of this land that is filled with life, we marveled at the falling house with its square shape, thinking about what is temporary and lasting, as well as the meaning of “residence” and the original form of the house. It took five years from the first site visit to create the final design, and another seven years to complete the construction.

Original form of the house

The discussion of the original form is important for understanding the nature of the phenomenon and shaping the present anew. The original form is a collective representation that exists in the subconscious. The original form of a house is based on the identity shared by the people who inhabit it, not the architectural substance. Ever since mankind decided to group up and settle down, a hearth has existed in the middle of collective homes. Gottfried Semper, a 19th-century German architect, also referred to the hearth as the first element of architecture. The hearth, which has been the divine focus in the consciousness of mankind for a long time, will be placed in the middle of the new house that is being built on this land and will create a new focal point for the family. With the owner’s desire for unity and harmony among the family members, who have scattered over the years, the house will be a place at which they can discover the meaning of family and community and reinvigorate themselves in nature.

Order and metaphor

Building the Joan-myeon house was a process of accepting and finding solutions to the conditions occurring within a limited space. The land by the river offered limited space for construction due to regulations, and there was not enough floor space for construction. Despite the spatial constraints, the main task was to plan a two-story house with river views from all rooms, separate spaces for four families, and spatial blankness to craft a weekend home. The morphological expression of architecture was not necessary, whereas simple and plain construction logic that can embrace the given conditions was. As a result, we sought to create order in the space by making the hearth as the center of the house and the family and metaphorically capturing the river's horizontality.

Divided horizontality

As soon as the family enters the house, the warmth of a burning fire welcomes them. Behind the hearth, the long open window facing the river supersedes the boundary between inside and outside, bringing nature into the house. The house has a divided floor composition: main living areas are arranged around the hearth in a row toward the river, and secondary spaces, which face the garden, are densely located. The floor has a strong horizontality in response to the river as the connecting corridor being placed between two functionally separated areas, with the living space, the corridor, and the secondary space being arranged in parallel. The divided horizontality is reflected in the elevation of the home, creating an intriguing contrast. The northern facade of the house across the gate has a functionally closed configuration. The house, which is located between the river and the land, becomes an object to view, and the waterside scenery subtly reveals itself from the building’s exterior, which heightens expectations of the house. As the southern facade opens horizontally toward the river, the house turns into the subject of one’s gaze at the river. A concrete lintel laid across a series of windows from the elevated portions of the house is a tectonic expression that supports the visually weakened brick wall with holes for programmatic needs, as well as a metaphor for the river and the land's horizontality.

일시적인 것과 지속적인 것

대지는 북한강과 남한강이 합류하는 서쪽 강기슭에 자리한다. 40여년 전, 젊은 시절의 건축주께서 집을 지으려 얻은 대지는 긴 세월 사람의 손길이 닿지 않아 오랜 수령의 나무들과 무성히 자라난 수풀이 녹음이 짙은 숲을 이루고 있었다. 수풀 사이로 난 좁고 긴 오솔길을 지나 물가에 다다르면 바람에 일렁이는 갈대밭 너머로 고요히 흐르는 강물과 그 위에 얹어진 정암산 자락이 한 폭의 수묵 풍경을 이루고 있다. 이른 아침 피어난 물안개가 태양빛에 흩어지고 무리를 지은 새들이 고요한 적막을 뚫고 물위로 날아든다. 생명의 기운이 충만한 대지의 끝자락에 소명을 다한 채 쓰러져가는 ㅁ자집을 바라보며 일시적인 것과 지속적인 것, 거주의 의미와 집의 원형에 대해 고민했다. 첫 대지 답사에서 설계를 매듭 짓기까지 5년, 그리고 건축이 완성되기까지 7년의 시간이 흘렀다.

집의 원형

원형에 대한 논의는 현상의 본질을 이해하고 현재를 새롭게 구축하는데 그 의의가 있다. 원형은 무의식 속에 존재하는 집단적 표상으로 집의 원형은 건축적 실체로 존재하는 것이 아니라 그 속에 살아가는 사람들이 공유하는 정체성에 기초한다. 오래전 인류가 무리를 지어 정주를 시작한 시점부터 화로는 집단적 거주의 한가운데 존재했다. 19세기 독일의 건축가 젬퍼 역시 건축이 시작되는 첫번째 요소로 화로를 언급한 바 있다. 오랜시간 사람들의 의식 속에서 신성한 초점을 형성한 화로는 새로 이 땅에 들어설 집의 한가운데에 놓여 가족들의 새로운 구심점을 형성할 것이다. 세월이 흘러 멀리 떨어져 지내는 가족들의 결속과 화합을 염원하는 건축주의 바램처럼 조안면주택은 아름다운 자연 속에서 가족과 공동체의 의미를 발견하고 마음의 안식을 얻어가는 장소가 될 것이다.

질서와 은유

조안면 주택은 제한된 면적 내에 주어진 조건들을 수용하고 해결하는 과정이었다. 강에 맞닿은 대지는 여러 규제들로 인해 전체 대지에서 건물을 놓을 수 있는 위치가 한정적이었으며, 건축 가능한 연면적 또한 부족했다. 여러 층위의 공간적 제약 속에 모든 거주영역에서 강을 조망할 수 있도록 배치하고 네 가족을 위한 각각의 독립된 공간, 그리고 주말주택의 공간적 여백을 담은 이층집을 계획하는 것이 주된 과제였다. 건축의 형태적 표현성은 지양하고 주어진 조건들을 담아낼 단순하고 담박한 구축논리가 필요했다. 집과 가족들의 구심점이 될 화로를 중심으로 전체 공간에 질서를 부여하고, 강의 수평성을 은유적으로 담아 내고자 했다.

이원화된 수평성

집에 들어서는 순간 빨갛게 타오르는 화로의 온기가 식구들을 맞이한다. 그 뒤로 강을 향해 길게 열린 창은 내외부의 경계를 넘어 자연을 집안 가득 끌어들인다. 화로를 중심으로 주요 거주 공간들이 강을 향해 일렬로 배치되고, 보조 공간이 정원을 면해 압축적으로 배치되면서 집은 이원화된 평면구성을 가진다. 공간을 연결하는 복도가 기능적으로 분리된 두 영역 사이에 놓여 거주공간-복도-보조공간이 병렬로 배치되면서 평면은 강에 대응하여 강한 수평성을 가진다. 평면의 이원성은 주요 입면에 투영되어 흥미로운 대비를 만들어낸다. 대문을 들어서면 마주하는 북측면은 기능적으로 닫힌 구성을 가진다. 집은 강과 대지 사이에 놓여 조망의 대상이 되고 수변 풍경이 건물 외곽으로 넌지시 드러나며 집에 대한 기대감을 고조시킨다. 남측면은 강을 향해 수평으로 열리면서 집은 강을 바라보는 시선의 주체가 된다. 조안면 주택의 주요 입면에서 일련의 창호들을 길게 가로질러 얹어진 콘크리트 인방은 프로그램적 필요에 의해 뚫려 시각적으로 약해진 벽돌벽을 공고히 다잡아주는 텍토닉적인 표현이자 강과 대지의 수평성에 대한 은유가 된다.